It was on the

warm up. I stood on tipped toes surveying behind a flake for a

last cam before running it out on unprotectable slab. I

never suspected the flake. It popped loose, a boogie board of sharp stone.

It hit me in the right thigh and rode me down. The rope caught me on the next cam, but the stone kept going. It pushed passed my legs, smashed my right foot

against the slab and crashed to the ground. My trusty climbing partner, Alex, was okay. The rope was intact. I had a deep knot in my right thigh. I couldn't feel my toes. Maybe the

numbness would subside and everything would be fine or maybe it was a mess under the cover of my pant leg and shoe. Alex eased me to the base. I gingerly removed my climbing slipper.

Blood pricked from the corners of my darkened middle toes like drops

of juice from bruised fruit.

It was my first

climbing trip of the season, the first since February. There was novelty in the war story of the 5k bushwhack out from the WV jungle, then there was just atrophy of

mind and body in summer.

We sat in the

concentrated sun of my backyard. There was something on the grill and we were

drinking beer. I hadn't seen my climbing friends in a while. First child rearing kept me away, then I was

sidelined by that rock. I was happy to see them. I took a swig.

"Patagonia in

December eh? " There was no way I could make it happen, but old ambitions

stirred.

I listened to the story of Alex and Spencer's new route on a

remote wall in Wyoming. I took another swig, the beer warm and sickly sweet.

By late August I

could painfully don climbing shoes. I had planned on a trip to Yosemite in the Fall before I broke my toe, but now I wasn't sure. If I was going to take time

away from family it had to be worth it, and here I had no plan, no partner and

only six weeks to train.

"Man, so yeah, I could die," I said to myself sitting in the window seat on the airplane to California, reflecting on my progress leading to this moment, finally on route to the big stone.

Previous efforts uncovered new facets in the physical regime or diet. I looked inward to my motivations and fears and sought a new level of discipline on this one. Part of my daily effort was to meditate on the fact that death might come at any time, by traffic or cancer or plane crashing on my house--as it did for my dear colleague Marie--as inspiration to arrive in the moment with zeal and appreciation for what’s truly important, having examined my fears so as to control them rather than otherwise. Yet, I could not deny, if I die climbing it has a different meaning than a plane on my house. I chose this path even while I have such precious things to live for. The question of why always returns.

Climbing used to be my crusade. I would spend as much time as possible out there,

stripping fears and supposed necessities, exploring adaptation to

extremes. A youthful part of me sought to spite the civilized, and show how I could be so hardy as to leave it all, author my own survival. I adjusted and bought

in to the usual vestiges of USA citizenry and have started to reap the rewards

of work and family: the face of my son after a couple days away, his cracking

jokes to get me to laugh, me laughing at his joke, but even more with happiness

at his reaching out to me, and him, my son, laughing again, happy at my

happiness.

I recalled a trail run long ago, breaking into a clearing to find 5 adolescents boys wearing bright, loose gym clothes and book bags with water bottles and accessory garments strapped to the sides. They were in the act of crossing a 12" caliper tree bridged over NW Branch Creek. Two had completed the crossing. One was mid-way, half crouched, clutching thick branches that obstructed his passage over the central trunk. One was tentatively beginning the traverse on the far end with a tall can of Monster energy drink in one hand. The last waited his turn.

"Think of God or imagine your family and go," instructed one of the two crossed boys.

"No, you want to think of nothing, clear your mind and just do it," said the other.

The conflicted boy turned to bail. I returned to my run and left them behind.

Yosemite. Morning. I filled our crusty camp pot

with cold water from a nearby spigot, turned up the gas on the canister stove

and sparked it with a lighter until it whumped and roared quietly and glowed orange. I sparked our second stove and eased the flame back as low as

it would go and placed our light camp fry pan on the flame. I added butter and coconut oil and let the fats melt and meld and simmer off their moisture. I

broke four eggs into the pan. I filled the hopper on my hand grinder with

coffee beans and braced the glass receiving jar between my legs and drew the

mill arm in circles as I listened to the beginning legato

sputters from the eggs. The sputters built with energy as I emptied the coffee

grounds into a paper filter. I poured steaming water from the pot over the loam grounds, which foamed with little rainbow bubbles. I

spooned avocado atop the eggs and finished the skillet with dribbles

of hot sauce.

There were hushed

chatters from the camp next door. They lacked the periodic swells of laughter and cackles you hear at night. The air was

fragrant with the smell of old pines and smoldering camp fires. Low-angled morning

light glittered off pine needles and illuminated a haze of smoke captured in

the trees. Rock walls loomed beyond, cupping the valley to create an ever present roar, the same effect as with a seashell to your ear.

There were hushed

chatters from the camp next door. They lacked the periodic swells of laughter and cackles you hear at night. The air was

fragrant with the smell of old pines and smoldering camp fires. Low-angled morning

light glittered off pine needles and illuminated a haze of smoke captured in

the trees. Rock walls loomed beyond, cupping the valley to create an ever present roar, the same effect as with a seashell to your ear.

We parked among throngs at El Cap

Meadow. I assumed there were many

places like this when I was young. Yellowstone, one of many parks, the Bad Lands, another weird landscape, Rushmore,

another monument. I would play with my boot knife trying to get it to stick in

a tree. I was looking for a practice. The search

brought me to climbing, which brought me back to wild landscapes, and now to really see them.

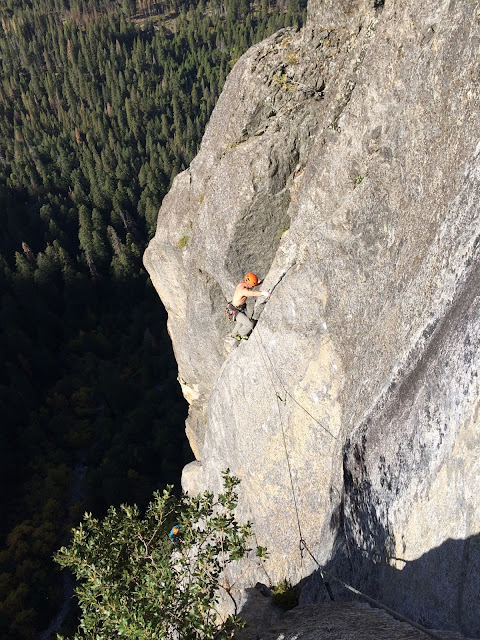

The next morning was cold. I wore

long Johns and a down jacket as we hiked the short way to

the base of the Serenity and Sons cracks behind the old Ahwahnee Hotel, now called The

Majestic due to changing of corporate guard and ensuing custody battle over

historic naming rights. Then it was hot in the direct light at

the base.

Dean and Nolan were there, the

two pale skinned programmers from the Bay area who followed behind us on the Central Pillarof Frenzy yesterday.

Dean and Nolan were there, the

two pale skinned programmers from the Bay area who followed behind us on the Central Pillarof Frenzy yesterday. "Hey, we get to share again, but we're now you're in the lead," I chimed.

Dean, the one with dark red hair, "Yeah, but I've been having dizzy spells. Not sure about this first pitch. You guys go first."

I flipped a bar of chocolate that would later melt into a mess in Alex's bag and bid Alex to choose which side, label or no, would fall face up. He won the call and first pitch.

It was low angled and followed a

seam that had been so badly beaten by the chromoly pitons of climbers in

the 70's that inch wide pocks beaded the seam’s length. The pocks were great

for pinching with two or three fingers stacked in one and thumb in

another, and jamming toes, but the sides were flaring and refused cams and nuts

for the first 40 feet. Alex expressed nervousness, but led well, stalwart as always. I followed and found the pocks to be very uncomfortable

on the feet.

This embodies a major challenge

for the east coast climber climbing out west. I trained well over the last year applying gymnastic strength training concepts to movement on

stone, yet nothing on the east coast prepares you for prolonged standing on

your foot sideways inserted in a crack. Small muscles in your ankle and heel strain and burn, and then you keep going until it

feels like hot knives. I felt kinship for the hero Achilles, godly powers all

over from being dipped in the river Hades, except for at the point where he was held.

The protection was better on pitch

two, a low angled hand crack pinching off to force a traverse into another hand

crack. I found the moves easy enough and enjoyed the delicate foot matching

puzzle on the traverse, but again the climb became a campaign of pain

management. I would fight to find stances where I could weight my heel and let

blood flush the toes, then wrestle to the next stance.

Climbing returned to the familiar

as I followed Alex’s lead through the crux. The arching slot received

just the first two finger joints, which locked tight upon a slight twist. The left

foot smeared on rough patches of crystals, the right high stepped, toe to edge

on the thin crack, and then there was a final long reach to a jug. It was steep

enough where weight was more on the fingers, and the requirement for focus shut out pain.

The sun broiled us as I led the

third pitch of never good enough thin hand jams. The word "albedo"

swirled in my head, and I wondered, "can you get snow blind from granite?"

At the belay, "I'm a grown

ass man [as Laura likes to tell me]. Do I want this? Is this even climbing,

this masochism?"

Following the next pitch I resolved

to call it at the belay.

"We climbed the tough bits,

now let's go down."

Alex was supportive.

The pain ebbed as we deliberated and the crack ahead looked too perfect. I grabbed the rack. It was so consistent

in the hands size that I had no choice but to space my few pieces of applicable

gear 3 or 4 body lengths apart, yet, the feeling of being connected to the

rock, exerting pressure just so, playing with balance, ease.

Alex swung to finish the last

pitch, which had a similarly aesthetic start, and then a wide section at the finish that

brought the foot pain raging back.

It was done. We rappelled the

route back to the pizza deck, drank a tall beer and retired to bed happy, but feeling like

old men.

We broke camp at our leisure the

next day. We had come to enjoy Housekeeping Camp where you each get a little

area to cook and sit, and a fire ring even, but they were shutting it down for

the season. We moved to Half Dome Village, the old Curry Village pre-corporate

overreach, which was denser with tent cabins and there was to be no cooking near

camp lest you attract hanta virus carrying critters or bears. Half Dome Village

was at least near the Pizza Deck where we ate most

dinners, and the Mountaineer's shop, which was useful for supplies. There were

also boulders to climb in the forest around the perimeter.

We wandered the forest. I found a boulder that looked easy. I grasped

the stone, leaned back on a straight arm, and walked my feet up crystal by crystal,

slowly finding balance with each move, up to a stable posture where I could

twist my hip and reach for the next glassy edge. The air was cool. It was easy yet complex enough

where I had to shut down my thoughts and pay attention, like in yoga. I

topped the easy boulder, four points of contact transitioning to two. Yellowed leaves spangled the pine needle floor. There’s

less strain once all your weight is on your feet, yet it feels more precarious

and you have room to think about how you don't want to screw it up.

We found more boulders. The good ones involved steep, under vertical faces with just wrinkles for foot and handholds.

They were about nuance and calibration in trust between body, climbing

shoe, and rock. Then some required full recruitment through crimped

fingers on sharp holds. We found the problems on Mountain Project and knew they

were of a grade we should be able to climb, but here they were shutting us

down, challenging our resolve not to try too hard on a rest day.

We had pizza and beer for lunch,

pizza and wine for dinner, and then retired to our cabin for whiskey.

The siren call of the rest day: you have time and start to feel good and it feels like cause for

celebration. Indeed, what's better than time and health?

Laying in my cot, ice and whiskey

sloshing in my coffee mug, a fire of good feeling and extroversion burning in

my gut, "You have to hear Eddie Izzard describe the fall of the English

Empire as a bunch of Englishmen responding, 'Do you think so? Is it really?'

You have to hear Hannibal Burress talk about jay walking in Montreal." And

I'd splash some more rye into the bed of ice in my mug.

I was a serious lightweight after

the last month of ketogenic diet and abstaining from alcohol. You eat mostly fat and as few carbs and sugar as possible on the ketogenic diet. I ate eggs,

sardines, smoked oysters, macadamia nuts, avocados, cheese, steak, salad, and cruciferous

veggies sauteed in Kerrygold butter and Trader Joes extra virgin coconut oil. The absence of carbs makes some part of you think you

are fasting. Your sense of hunger decouples from urgency, you lose

any semblance of bloat and your energy comes from a deep

steady stream that leaves the surface of your mind a still pool. Abstaining

from alcohol is where you gather with your friends on a Friday night and drink

water with a wedge of lemon as they drink ferment. It's hard to defend to others and yourself at first, but then you feel

like a fish jumped from a stream to a bank with a good view,

who sees the stream from the outside for the first time in a long time.

I woke in the middle of the night

with my heart beating harder than proper.

I'll often wake in the middle of the night and visualize a climb or topic

of interest, or I’ll scan through my body releasing tension or count

breaths. Here, though, I just laid there, dull mush.

Our machine took a long time for

action in the morning. Alex hit snooze no fewer than ten times. The alarm became

absurd, no longer a tool for punctuality, it became one for self-flagellation. You

don’t actually rest between eruptions of jangling scales, yet it

feels irresponsible to turn it off. There's an unspoken hypothesis that you can cleanse yourself with torment. Discomfort will saturate the

system to a threshold beyond which you'll burst into action, fresh.

Hiking to Voyager, steadily up a

thousand feet or two of rocky stream bed, I felt shaky and tired.

The first pitch started with crumbly rock acknowledged by the developer with two bolts in the first thirty

feet where protection was possible, but "why sweat it here" was the

message. Then I was suddenly pumped in a sustained corner of clean rock

higher up. Edges had given way to paltry smears as I stemmed up the open book.

I gained progress by reaching high into the crack in the corner, laying back to

one side, pushing hard with my feet smeared on the other. I would jam the fan

of smaller toes on my lower foot into the crack and pull to locked biceps

to peer into the crack and place gear and clip my rope. There was a thankful

stance where I stood on a rib, but the hand holds remained elusive, just an

undercling at my navel and flake at full extension above where I could just fit the tips of pinky, ring, middle. I thought I'd pump out and take the fall, but I noticed my

heart rate diminish a hint. The pump would subside.

I was still shaky and slow leading pitch two, but my confidence grew. There was a low angle gully up to a flared chimney

obstructed with a roof. Spanning the chimney with stems brought me through all

but the roof, which I laid back, then mantled to a ledge.

"The Incinerator,” pitch 3, the crux of the route stood above for 80' of perfect left facing corner with a

flared and rounded off-finger sized crack. I began with my right foot pressed

wide right to a sharp seam, left jammed in the crack, and I leaned back with

both hands latched to the crack edge, arms straight. I pulled nose to the crack,

spine stiffly bending into a parenthesis to peek into the space, gauge size,

plug gear, clip rope. I leaned back again and shuffled my hands and feet. The

tension in my core flagged in random spasms and my feet slipped. I countered abruptly and evened the tension. I was deeply pumped, but found success over

50' or so, through enough iterations where I thought I had it. The sharp

seam wide right tightened to the corner, my base of support narrowed and pressure on my arms increased. My core flagged again and it was enough to

spit me from the face, just a few moves from the end of

difficulties.

From there I followed Alex for 3

pitches.

There was the second crux, "The Boulder Problem." Alex traversed a ledge 20', clipped a

bolt, and completed long reaches through face holds to the base of a hanging

corner capped by shallow overlap. You had to work your way just under the

overlap and work your feet high on nubbin smears as you underclung the overlap and

reached for a jug.

Then there was the face traverse

pitch in the sun, the wall like the side of a funnel overlooking a clean 600'

to the base, micro edges on glassy rock. Yesterday's bouldering on thin holds

was the perfect preamble. I followed the pitch confident to the point of almost

blowing it.

I luxuriated in the knowledge that the worst was over. We'd risen

from hypoglycemia and negotiated the difficult route.

Psyche was high over pizza that night, but I was wrung out. The rest day celebration was too much and detracted from the

day's climb. We'd done it in respectable style, but I sought a new expression of personal best on this trip. We had one more rest day, then we would attempt the true test, the climb I've read about in climbing lore for 10 years, the Rostrum.

I threaded a rope end hanging from the previous rappel through the last anchor bolts on the way down to

the base of the Rostrum. I put my weight into the rope as the threaded end slithered down the rock and the other hoisted to the anchor above till it cleared then snaked and

whipped to join the other on the ground. I pulled a large bight of the hanging doubled rope and trapped the slack with a dusty bare foot against

the ledge, rigged my rappel device, leaned

back to weight and test the system, detached my personal tether and slid down

the rope.

Leaning back I could see across

to the base of the route. The second of a rope team was just getting started on

the first pitch and another team waited in queue.

Alex descended after me and pulled the rappel rope as we acquainted ourselves with our new friends. There was Marten, the nimble financial adviser from Bavaria on a two year climbing sabbatical before

settling down with his girlfriend. He wore a #5 BD Stopper on a necklace. And Daniel the lovable Australian, blond, tall and lanky, already a committed dirt bag on permanent road trip after climbing only a year.

A loud crack of a rope

whipping down from the approach rappels sounded. Yet another team landed and hiked to where we waited.

"Hey, it's you, we shared

that route yesterday," Marten said to the first newcomer.

He was thin and wore a dirty white cotton t-shirt. He coughed.

"Oh yeah, and you have that

cough. I thought yesterday, how terrible to have a cold on a climbing

trip."

"It's cystic fibrosis, not a

cold, but it is terrible."

"What's your name?" I

asked.

"Claus, from Belgium," he

said with a voice rough as if he'd been a smoker, “and this is Rafael from Germany,”

he said of his bearded partner who had finished pulling their rope.

"What's cystic

fibrosis?" I asked, bracing for a difficult truth.

"It is a genetic disorder

that affects the mucus in your lungs and digestive system. It makes you

susceptible to infection and you generally only live to your early thirties.

But climbing helps, sport helps."

"It is a genetic disorder

that affects the mucus in your lungs and digestive system. It makes you

susceptible to infection and you generally only live to your early thirties.

But climbing helps, sport helps."

Claus looked to be in his early

thirties.

Eventually it was our turn to

climb.

Alex dubbed the character of the

first pitch as "necessary." He had run it out through the finishing

chimney and not gotten suckered into the awkward yet more protectable depths.

"A little spice on the first

pitch is good for the head for the rest of the day," he commented.

I lead pitch 2 with a beginning down climb and traverse to a techy thin finger

crack "test" with threateningly sharp fins to the side and wave of

warm orange stone above.

It ended with a narrow stance and

gear anchor. Claus approached from below as I belayed Alex’s lead on pitch 3. He pulled

off to the side to wait to set up his own gear anchor.

"How long is your trip?"

I asked.

"Two months. I started a

month ago, but had to fly home in the second week to attend my sister's

funeral. She had cystic fibrosis the same as me. She was 32. She always wanted

to reach 33. That was her goal since she was little, just an arbitrary number

she picked. But I didn't get to be around her. The bacteria in my lungs, they

said if she was exposed, it would be bad for her. I wore a mask if we were in

the same room. Eventually they moved her to Greece, which she liked."

There was no hint of sadness or

regret in his voice. He spoke evenly, simply stating the story of his

trip.

"My parents. No other

siblings. They stopped with my sister and me given our condition. They call you an orphan if your parents die when you're young. You're a widow if your spouse

dies. There is no word if your children die. It's not supposed to happen."

Suddenly, my thoughts on living in moment, as if any day could be my last felt, not misdirected, but utterly shallow and naïve compared to Claus's reality. I was but an infant trying to grasping the weight of the moment. I felt sadness and anger for Claus.

Suddenly, my thoughts on living in moment, as if any day could be my last felt, not misdirected, but utterly shallow and naïve compared to Claus's reality. I was but an infant trying to grasping the weight of the moment. I felt sadness and anger for Claus.

The rope came tight to my waist.

"On belay Dan," wafted from

above.

I broke down the nest of my gear anchor,

cleaned it to my harness and started to follow the pitch.

There was a tenuous layback transition through a roof to a thin hand crack in an acute dihedral that widened to cupped hands,

and a white bulge at the top with the appearance of jugs, but nothing secure, just complex sequences and delicate stemming. There was a piton for

protection after which Alex had run it out to the belay.

"That took work. Nice

lead," I told Alex.

Alex yelped and fell to a

crouch and grabbed his foot. There was a bee under his big toe. He pinched it between thumb and first finger and flicked from the cliff with

gritted teeth. It was his second sting of the trip. Now pain and threat of

immune response joined our uncertainty about finishing in the dark.

At the very least we’d climb the crux, up next. I led past a ramp to the base of clean shield with a finger sized fissure. I committed to a chess game of small foot holds, and gambling on sequences. There were good finger locks, but you had to be patient to find the right ones. There were shallow toe jams you had to set with pressure just so. I was surprised to find good stances and gear.

At the very least we’d climb the crux, up next. I led past a ramp to the base of clean shield with a finger sized fissure. I committed to a chess game of small foot holds, and gambling on sequences. There were good finger locks, but you had to be patient to find the right ones. There were shallow toe jams you had to set with pressure just so. I was surprised to find good stances and gear.

Confidence and calm washed over

me at the top of the pitch. Looking down to celebrate with Alex, I noticed that

Claus and his partner Rafael no longer trailed behind us.

We waited for the backed up parties

ahead to progress.

Pitch 5 through the bright orange

corner, pure joy in perfect jams and stemming edges, dancing between the two

forms, laying back a roof on smears to the belay where Marten and Daniel yipped

and yelled.

Pitch 5 through the bright orange

corner, pure joy in perfect jams and stemming edges, dancing between the two

forms, laying back a roof on smears to the belay where Marten and Daniel yipped

and yelled.

Pitch 6 with the infamous

off-width crack, trying to postpone the terrible business by milking stems in a

steep corner that wanted to spit me off, then, suddenly, being committed to the

wrestling match of hand stacks and knee jams, heat and sweat building, knee

becoming raw.

Pitch 7 in

the dark, bomber hand crack, long certain moves through the last crux, up into an alcove glazed white

with peregrine excrement.

It clicked somewhere mid-route,

being tuned in to the granite. It had everything to do with a certain pacing. I needed to pause and wait a second to fully arrive, to feel through the rubber

of my shoe, through the tape on the back of my hand, through the fire of

raw skin. I had to acquaint myself with each hold and nestle every surface

between the sharpest crystals. I had to duck my head close to where my feet were about to be and remember the little coin edges and rough patches for

when I stood up to use them.

On the last pitch, I traversed below a large roof in the bubble of my headlamp, across the urate painted ledge

to a Gunks-style grab-a-jug-and-heave onto a high foot roof move, back into an offwidth

crack and walking a #5 cam ahead of hand stacks and raw knee jam. I found my

eyes wide open, pupils like black holes, irises eclipsed. Moonlight and stone

patterns poured in. High over my gear on the last face move on friction crimps

to the final mantel, energy tingled throughout my body. I climbed through the black

holes. There was incredible lightness.

The kids crawled into bed the morning after my late return. 2 year old Finn hugged me in the dark and 1 year old Owen sat on the corner blinking in disbelief. Then there were hugs and heads nuzzling into my side through the rest of day. My body was weak and mind foggy, but there was only the need to revel in family. We enjoyed the sun in the backyard that afternoon. I took a swig. The beer was crisp and refreshing.

The kids crawled into bed the morning after my late return. 2 year old Finn hugged me in the dark and 1 year old Owen sat on the corner blinking in disbelief. Then there were hugs and heads nuzzling into my side through the rest of day. My body was weak and mind foggy, but there was only the need to revel in family. We enjoyed the sun in the backyard that afternoon. I took a swig. The beer was crisp and refreshing.

Beautifully written--eloquently concluded!

ReplyDeleteIntense! Well done my friend. But what is your advice to the kid on the tree? - Ben

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteautobet เว็บเดิมพันที่ครบวงจร หากใครที่กำลังมองหาเว็บเพื่อการเดิมพันที่น่าสนใจ หรือใครที่กำลังมองหาช่องทางการทำเงินแบบง่ายๆ ทางลัดที่ autobet

ReplyDelete